On April 24th, EVE will alter the rules of the game (a "patch" as they call it) which will radically change the economy. Basically it means players will have to create more things themselves, rather than just getting it from killing computer characters. This increased focus on player production (and it is already quite focused) will increase the demand for the game key mineral: tritanium, or trit.

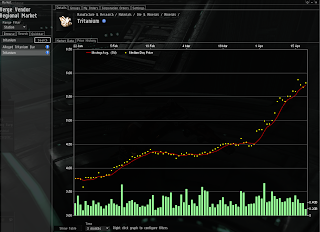

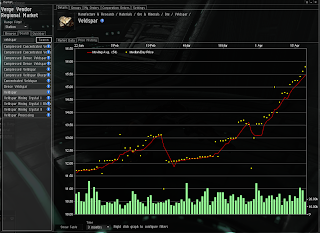

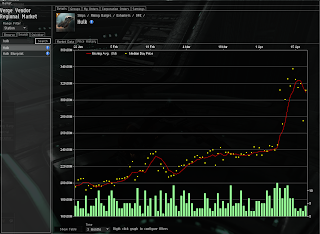

When the patch notes came out earlier this month, trit prices exploded, along with veldspar (an ore that's refined into trit) and hulks (a ship that's really good at mining veldspar). (All screen shots were taken on April 19 at about 19:45 EVE time, or 3:45 EST, in the game region of Verge Vendor.)

(That recent dip in hulks is interesting; I'll get to that in a sec.)

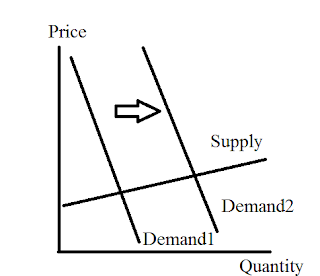

As predicted by basic economics, the price is rising. If the demand shifts out (more people want something), the price will rise. This is why I, and many people in EVE, are mining. Prices are really high. But a friend of mine who plays insists I shouldn't sell my veldspar now. I should sell it after the patch is released because then the price is even higher.

But if the price is over-inflated, as I think it is, then this is a horrible decision. I should sell while the price is high. Like a house in 2007, get out while the getting's good.

It's hard to tell if something is a bubble or not. Is this price increase just the beginning? Or are people holding on to the veldspar and trit because everyone assumes the price will rise, only to find it dropping when they want to sell. I'm inclined to believe the latter for the following reasons:

Elasticity. This is the measure of how sensitive the supply and demand curves are to price changes. It's really easy to mine veldspar. Thus the supply of veldspar is elastic: a small change in price will radically increase how much people will bring to market. This price increase will be small.

But the price increase isn't small. It's gone from from 4.50 to 5.75, a 27.8% increase. The price is probably too high.

Quantity. According to the little model up there, quantity should be off the charts. But the amount of trit sold (seen as the green bars) is (slightly) falling. Hulk sales, on the other hand, saw a jump in quantity when the patch was first release. They're the first thing you'd buy if you're a semi-experienced player (thus able to fly one and can afford one) and want to respond to veldspar prices. But we're not seeing veldspar and trit quantities rising. People are holding onto them. And now that the hulks have been bought, quantity's fallen and price is beginning to, as well. (Though I don't want to read too much into a short-run dip in a price.)

The Winner's Curse. Estimations are normally distributed. Some people will overestimate the future price of trit and others will underestimate it. The person who over estimates the most will pay the most. They will win the bid and they will regret it. Prices are driven by the winning bid so things will seem more valuable than they are. And this is made worse because...

Prices are correlated. EVE uses an English auction: if you're buying you place your bid and the high bid will buy the auction. You can up your bid if you want. But people tend to use other people's prices as information. If someone keeps outbidding me, then I might think that they know something important I don't so I outbid them. They then use my bid to think I know something they don't so they outbid me. Around and around we go until we wise up and the market crashes.

This prediction comes with caveats. (1) I may know that the supply curve is elastic, but I don't know how elastic. I may know the demand will shift, but I don't know how far. It's entirely possible that a 27.8% increase is modest and this is just the beginning. (2) If players can't sell their trit at a price they want, they will probably just hold on it. You don't have to pay a store fee after all. Thus prices might not crash. But if they don't, quantity sold will.

So I could be wrong--I'm not selling all my veldspar now--but I'm selling most of it. In less than a week, I'm going to look either really smart or really dumb. C'est la vie.